Kinngait is located on Dorset Island, one of a group of islands off the southern coast of the Foxe Peninsula. In 1913 the Hudson’s Bay Company opened a trading post here and from 1939 to 1949 the Baffin Trading Company operated a competing trade. In the early 1950s, the catchment area of camps trading with Kinngait ranged from Amadjuak Camp, 280 km to the east, to Nuvuqjuaq Camp, 190 km up the west coast.

Part of Kinngait village with Kinngait Mountain

(Photo: Ansgar Walk, May 1997; credit: Wikipedia)

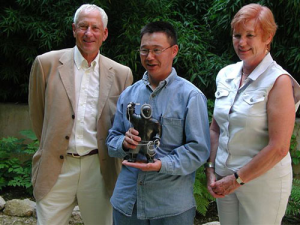

When James and Alma Houston arrived in Kinngait in the spring of 1951, they were delighted with the artistic potential they found in the camps around Kinngait. In contrast to the eastern shores of Hudson Bay, artists like Osuitok Ipeelee had already made a name for themselves with their ivory carvings. In fact, Houston was impressed with the overall art experience in Kinngait. He explained:

“Cape Dorset was quite different from either the east or west coast of Hudson Bay. I am still not sure why that was – perhaps because word of our attempted encouragement of Eskimo art had gone before us. I found the Inuit trading into Cape Dorset to be the most exciting, friendly, volatile, and certainly, the most talented Inuit group I had ever met. The Dorset people began right away to bring in carvings and seemed delighted with their payment slips that gave them instant trading power atthe Hudson’s Bay Company. The Baffin Trading Company had just disappeared after some years of somewhat bitter competition.

Perhaps we were fortunate that there was so little walrus ivory available in Cape Dorset, for the carvers immediately returned to thatage old medium, soft stone. Not too soft, mind you, for the carvers hate the kind that while being worked will crumble or crack apart, destroying many hours or days of work. The first stone we found in Cape Dorset was rather dark and coarse. It had the look of granite and came from around Kiaktook and down the fjord near Tessiakjuak. Manumi, the carver, found a small but good deposit near the north camp at Nuvudjuak.

Only a number of years later did we finally discover the rich deposit of a green stone (serpentine stone) just east of Amadjuak. This stone was perhaps of the finest quality ever discovered in the Canadian Arctic. It had a deep green jade-like lustre and would polish beautifully. All the large early stone blocks used for printmaking came from this deposit, alas, , is now nearly depleted.” (Excerpt from ‘Early Masters: Inuit Sculpture 1949-1955’, p. 135-136)

After collecting carvings in Kinngait for a summer, the Houstons left the settlement aboard the C.D. Howe on August 14, 1951, to continue traveling around Baffin Island to find possible artists and artworks in other settlements. The new carvings – especially those from Kinngait – soon attracted international attention. The extraordinary exhibition “Eskimo Art”, shown by the National Gallery in Ottawa, opened with a gala on January 18, 1952 and included 69 works of art, 45 of them created by artists from Kinngait.

James, John, Samuel, and Alma Houston in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, 1960.

(Photo: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton, credit: Art Canada Institute)

In November 1953, the Houstons were recruited by the federal Department of Resources and Development and continued to build the art program alongside the Kinngait artists, with whom they had a deep affinity. With great commitment and empathy, they also developed the two-dimensional art sector with drawings and, in part, the resulting graphics, in addition to the three-dimensional sculptures. When they left Kinngait in 1962, they had found a competent successor in Terry Ryan (1933-2017).

There are so many well-known artists in Kinngait that a list would not do them justice. Some of them will therefore be presented in future posts. For a small sneak a peek, you can find works of art from Kinngait by clicking on the link.

Sources of information: “Early Masters: Inuit Sculpture 1949-1955” (by Darlene CowardWight, The Winnipeg Art Gallery, 2006), “Kinngait” (Wikipedia) and „Pitseolak Ashoona“ (by Christine Lalonde, Art Canada Institute)